REFLECTION

Tracing a Subtle Feedback

Painting as a Language of Participation

This reflection on painting reexamines the process of observation as an active form of interaction. It is supported by theories on perception, Art Therapy, and raises an inquiry on the categorical distinctions between symbolic dialogue and social practice.

This essay is published in the third edition of Reflections a journal for the MA Fine Art in Camberwell College of Arts, London. To visit the published version, click here.

Probably the only thing one can really learn, the only technique to learn, is the capacity to be able to change.–Philip Guston

Having perceived how small, indifferent signals seem to fit together into significantly charged symbols, I constantly find myself recognizing how far beyond our rational grasp lies the system that meets them. For at least a century, Surrealists have been putting accidents and indeterminacy to a formative use, channeling into a ‘universal order beyond any construct posited by Western casual and logical thought’ (Watts, 1980, p. 4.) Although they made manifest some of their methods, the process by which I’ve found myself tuning in while painting has proven difficult to identify and practice sustainably. Perhaps for this reason, this essay follows an effort to identify parameters that are essential painting as a spiritual practice, and map some of the observed correspondences as some evidence of the systems operating beyond reason. Just by identifying the formal methods and materials present, the symbolic overtones carried with every work also start showing more and more.

Identifying Parameters

Throughout the summer I painted onto five (5) canvases I bought, sized, worked on and stretched, plus two (2) small format and unevenly primed paintings offered to me by M–artist and my host–upon my arrival at a seven (7) week artist residency in Tbilisi. All the works were painted with oils, only one (1) of them wasn’t exhibited, three (3) have been sold. Only in two (2) out of the (7) mentioned paintings did I have an image as a starting reference. For the rest I applied colors in a specific consistency against a specific surface without a preconceived idea of the forms to make or the place to apply them. This led me to unpredictable problems that required unique solutions according to what I noticed happening.

All the smaller formats–M’s two canvases–were painted on in a number of attempts by which I covered the whole surface with coat of fresh paint, some becoming resolved in the first one, or alla prima. Having outlined the physical parameters, I’ve also identified how their corresponding symbolic properties underline in the output as well.

During sustained periods of intense involvement, I noticed patterns of signs which were feeding back and forward towards symbols emerging spontaneously; that is, with no rational intention. Like whispers, these symbols reflected something back to me, like feeding relevant information which bypassed the cloud of thought and learned tendencies. Reflecting on this has allowed me to identify paintings as direct mediators surrounding the observers’ life situation. I will hope to trace some of the most significant signals pointing towards meaning in an effort to expose a network made visible through painting as a process of transcendental observation. I’ve come across relevant guides by engaging with theories of perception, art therapy, and social practice.

The Problem with Categories

Ten years ago, as an undergrad, I attended a panel discussion with Luis Camnitzer, a leading Argentinian figure in conceptual art and art education. While answering questions he declared that ‘if you hang your little landscape at the art fair and sell it, you won’t be impacting society in any way whatsoever.’ In spite of this, somehow I have been led to consider an essentially social role in the intimate, reflective process of confronting the painting as both a maker and an observer. Maybe much like the slow correspondence between those who anonymously exchange letters, both the makers and the observers exchange ambiguous signs and symbols with themselves as well as with each other. A broken code is offered via the sensuous experience, waiting patiently for a recipient to reconfigure and accept it unknowingly. More recently, certain experiences and authors have led me to acknowledge how images and symbols are recreated according to our individual history and our present circumstances as spectators (Rancière, 2009.)

In Education for Socially Engaged Art; A Materials and Techniques Handbook, Pablo Helguera seems to follow Camitzer’s categorizations. He mentions the ‘community of narrators and translators’ who project their own personal experience onto the artwork that Jaques Rancière celebrates in The Emancipated Spectator (Rancière, 2009). Even then, Helguera categorically separates ‘direct’ and ‘actual’ practice from that of the visual arts, labeling their symbolic, paced reach as ‘nominal’, ‘passive’, and ‘hypothetical’, as though they barely involved any form of participation, much less a form of social involvement. He largely defines social engagement by comparing it to what it isn’t in an effort to develop the ‘nuts-and-bolts’ technical manual ‘that [can] guide practitioners in understanding the elements of their practice and achieving the results they want’ in the same way it’s already been made available to ‘painters, printmakers, and photographers’ (Helguera, 1991, p. ‘x.’)

In any case, Helguera’s manifesto made me question the need to gather all the parameters of painting as though one could expect ‘achieving results’ in what I experience as an essentially indeterminant build-up. How could I enunciate painting, which is essentially based on abandoning instructions, expectations, and the illusion of control as a starting premise? Unable to dictate painting as a method with a set of definitions to consider, for example, while walking inside a dark cave full with fluid, organic forms, I’ve opted instead for describing the events that first came to mind as a way of retracing my experience back to the embodied language. That is when the body knows how to act, and its where personal meaning derives from.

Still looking for the ‘elephant’ that the tour guide referred to while pointing at these forms. Prometheus Cave. Tsqaltubo, Georgia (Personal archive.)

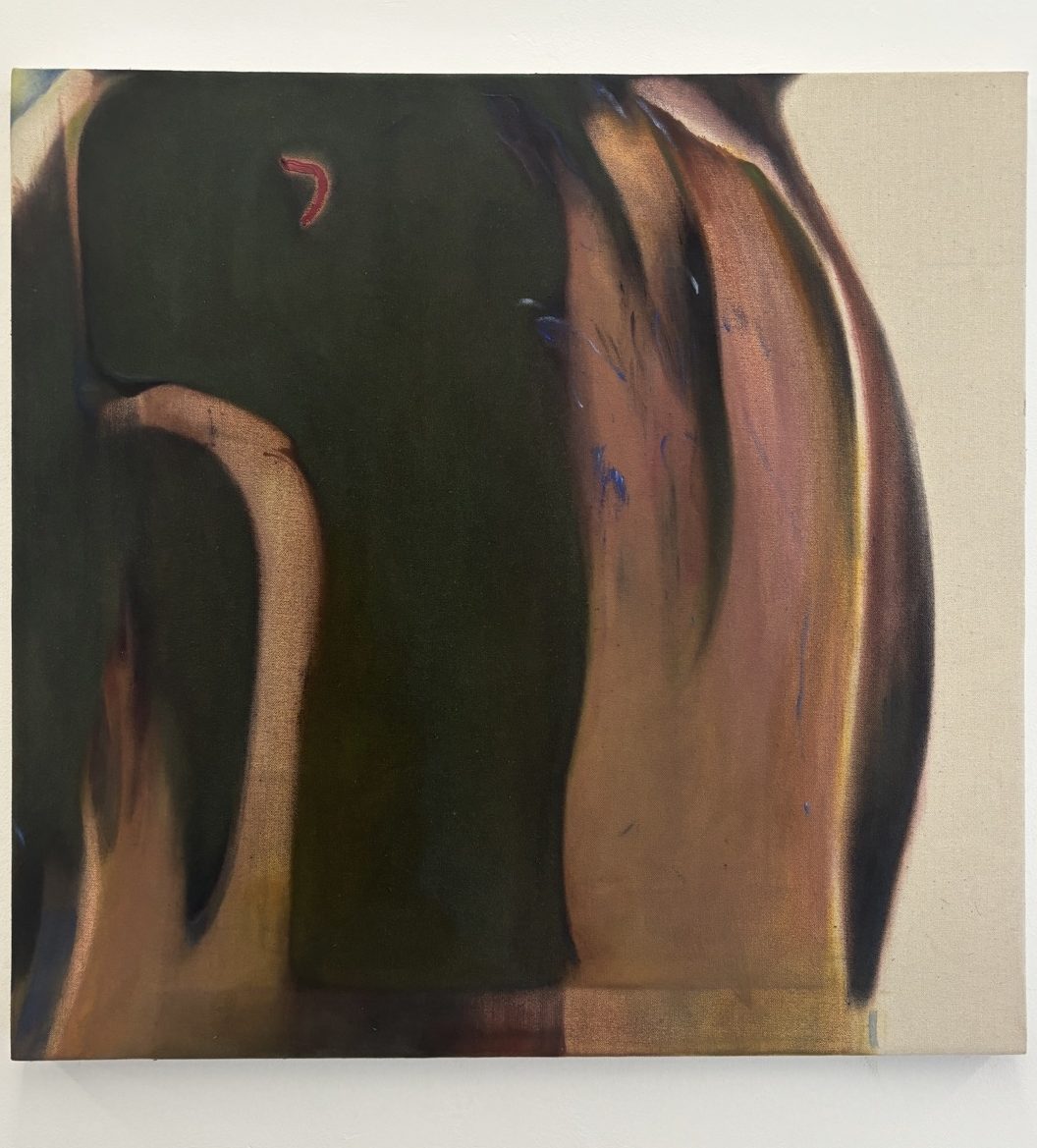

Prometeo, 2024. Oil on cotton canvas (97 x 78 cm.)

Embodied Practice

Around 1983, the Portuguese artist Paula Rego (1935-2022) painted a series of large works where she ‘engaged with her childhood passion of painting as play’ (Nick Willing in Paula Rego: Letting Loose) where, says Michael Ajerman, she ‘sinks her teeth’ on the works: ‘There wasn’t any clear narrative–and everything seemed to basically fly all over the page and kinda find itself the way that it develops along the way’ (Ajerman, 2024.) He refers to the pictorial act as a physical, perhaps mechanical, but mostly feral, instinctive action, when relating to a process which ‘develops’ organically, spontaneously, by itself; as if it had a life of its own. In the creative act, I also agree, the work eventually starts to happen irrationally and even involuntary.

Amongst the chaotic compositions filled with forms that seem to sprout out from and back into ambiguous fields of flat pastel and off-white colors, one starts to identify poor and wicked characters seemingly bound to a kind of infernal garden of earthly passions and vices. The son of the artist, Nick Willing, said ‘these paintings, perhaps more than any others, helped to understand herself and those closer to her’ (Willing, op. cit.) It’s like the paintings themselves reflected an otherwise intangibly heavy burden being carried unconsciously until until managing to ‘bite’ through them. Also, Willing’s comment points to the idea of painting as a curative experience which led to a form of understanding–or catharsis–by which she might’ve reconciled with her position in relation to herself and the people around her. Confronted with the need to situate this non-verbal, embodied, intuitive process, I started regarding the significance of meaning more closely.

A figure wearing a jester’s hat appears in self-punishment. Paula Rego Untitled (Detail) 1983. Paula Rego: Letting Loose at Victoria Miro Gallery. (Personal archive.)

A figure looks begging at jester a who’s feet are bound to a pillory. Paula Rego Untitled (Detail) 1983. Paula Rego: Letting Loose at Victoria Miro Gallery. (Personal archive.)

A figure looks begging at jester a who’s feet are bound to a pillory. Paula Rego Untitled (Detail) 1983. Paula Rego: Letting Loose at Victoria Miro Gallery. (Personal archive.)

A fortunate number of experiences, references, and interactions have struck a feeling like we’ve grown accustomed to hold reason more closely than emotion. As a way of confronting this, I’ve began considering meaning as something which perhaps holds an inexplicable value, much rather than something that is understood. In his French radio essays in 1948, Maurice Merleau–Ponty argues how Decartes guided generations towards a circling, abstract trap by pursuing the extreme of reason. By envisioning the alternative, and accepting the tutelage of perception in things, he gathers ‘it is impossible to separate meaning from their way of appearing,’ and so he argues that, in this life, the essence of an object of interest involves a closely entwined interaction between the way in which his object of interest performs its function and our experience of the object’s accidental properties’ (Merleau–Ponty, 1948, p. 94.) In my understanding, Merleau–Ponty would perhaps appeal to describe–much rather than defining–the thread of ‘silent signals’ by which the experience acquires a form of intrinsic value.

Rather, as in the perception of things themselves, it is a matter of contemplating, of perceiving the painting by way of the silent signals which come at me from its every part, which emanate from the traces of paint set down on the canvass, until such time as all, in the absence of reason and discourse, come to form a tightly structured arrangement in which one has the distinct feeling that nothing is arbitrary, even if one is unable to give a rational explanation of this.

– Maurice Meleau-Ponty, 1948, Classical World, Modern World, p.72

Art Therapy as a Guide

Although popularly discussed in perception theory, for some time I’ve regarded embodied knowledge as a blind, subtle process difficult to put into words, including after using a theorist’s. How might one ascribe a special meaning in a visual challenge that starts out with no conscious image, narrative, and happens automatically, or unintentionally, as mentioned earlier? During my course I’ve unsuccessfully stressed how painting really occurs in a form of contradiction; once we become absent. As I pulled out Helguera’s Handbook from the shelf, another blue, small book stuck with it and followed behind On Art and Therapy; An Exploration, by Martina Thompson. It started out like this: ‘How we come to approach our work is often a matter of chance’ (Thompson, 1989, p. ‘1.’)

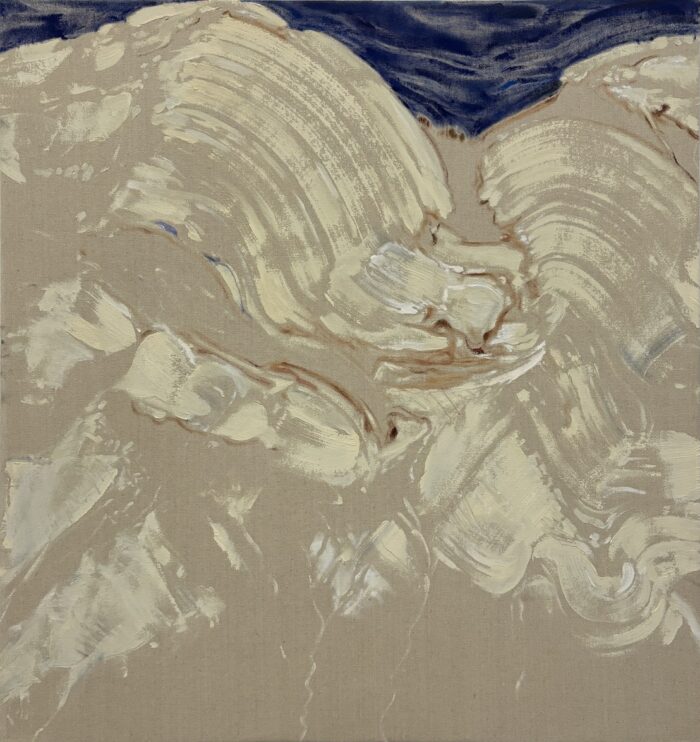

Nearby Objects, Surrounding Space / 2024 / Oil con canvas (72 x 70 cm)

Nearby Objects, Surrounding Space / 2024 / Oil con canvas (72 x 70 cm)

In her exploration, she tells her story as art therapist and a painter while also holding a historical perspective. In her analysis on the creative process, her acknowledgement of Anton Ehrenzweig’s second phase of The Hidden Order of Art felt to me like the closest of all descriptions of the painting process:

It is the ‘integration of the material [unconscious parts] in the picture by means of Dedifferentiation–defined as a receptive watchfulness, a dispersed attention; the use of the primary process as a precision instrument for unconscious scanning, a holding before the inner eye a multitude of possible choices’–until a hidden order becomes apparent.

-Anton Ehrenzweig in Thompson, 1989, p. 63.

Much like Ehrenzweig’s, Thompson includes an array of poetic, spiritual, philosophical, and scientific perspectives by which the untraceable instants of such a process become identified. By reading her, I have become relieved to find so many words and fields describing the indeterminacy of painting so openly and yet so clearly; a process which otherwise has been mostly introduced by normative manuals and manifestos which quickly become limited by their specific time and perspective.

Considering the methods and effects of such a practice, Thompson references her mentor, E.M Lyddiatt, on Carl Jung’s approach in viewing experience as the most important thing in ‘getting a valuable feeling out from the unconscious towards a restorative attitude into being’ (Thompson, 1986, 17.) By engaging with Active Imagination, experience ‘allows fantasy to take shape’ (Thompson, 1986, 18.) Although Jung categorically believes that such curative practice is insufficient as it requires an essential form of ‘integration’ and ‘moral assimilation’, I would like to make the case that the painter’s practice involves a specially inherent process of self-reflection. It is individual, as well as social, and it’s where the all necessary evidence needed in order to transcend beyond oneself is made available, or rather tangible in the trace left from that experience.

It’s really fascinating to find that the restoration taking place in the creative experience comes from a physical manifestation of a deeply rooted, raw material stored within. Of course, build up of raw material gathers a emotional baggage. But unless channelled somehow, it usually hides behind the maze of abstract thoughts and amassed feelings. It is accumulated and silently manifests through the aching social experience with ourselves and others until it can be fully and directly witnessed in traces by which the symbolic becomes material, and with it apprehensible.

Regarding Ajerman’s observations of Rego’s method while painting her large-early-80’s-works, he mentions her cautionary interpretation of a specific accident while visiting Henry Darger’s apartment in Chicago–that is the place where he used to live, paint, and the actual resting place of his thirteen-volume (13) work. Having found an inspiring dialogue with the sinister atmosphere in The Vivian Girls, ‘somehow, at the door, it slammed on Paula’s arm, on her hand, and really injured her; and she took that to be a sign basically saying that her version of the series was now over’ (Ajerman, 2024.) Considering how Rego decided to stop working on her version of Darger’s work as a response to ‘forces’ outside of herself ‘basically telling her what to do and what not to do’, suggests a longer reflection by which I would like to further discuss our context, outside of physical body, as a part of and extension of our embodied selves.

Following the thread of my recent practice in painting, I would like to introduce how the willingness to depart from a chosen route of action as a form of responding to internal–as well as external signals–leads to personal transformation. The following personal account is an edit of the press release which welcomed visitors along with an offering of traditional food and wine into my final exhibition during my artist residency in Georgia.

Moments before the private view of Dark Night in project space at Fabrika, Tbilisi.

Dark Night

Tbilisi 13.09.24 (Edit)

It’s hot, and I’ve been falling asleep later and later. The sounds of raucous Ninja Kawasaki bikes and customized race cars speeding up Pekini Avenue and down Merab Kostava Street surround me in the eighth (8) floor of the soviet compound at Tina losebidze Street. It feels familiar to say ‘I tried sleeping through it’ on my studio bed, the couch, on the floor, and then over the NIKE yoga mat I got from TOPSPORT around the corner. You’ll be constantly rattled out of ease until almost morning, when the sun’s suddenly high up again and it gets too busy with traffic for so many people to speed like that. But then the heat prevents you from crashing anywhere, even after a restless night. ‘They’re keeping me awake on purpose’ was a circling, delirious thought. I refused to take action beyond laying, in a tense build up of tolerance, shutting myself in, waiting for wifi and ease while sliding my phone and contemplating illusions of vaguely comforting alternatives: ‘This is already halfway to Nepal;’ ‘Someone said something about flying directly to Thailand from here;’ ‘There’s even enough time to even go home before getting back to London.’

Without the bold daring to part with his own identity, a human, as well as a city, is doomed to repeat the same experience in terms of its spaciality. The risk of giving up identity, the risk of change with an uncertain outcome, is a precondition of freedom. A cosmopolis creates spaces for human beings to transcend their own limits, to fulfill or realize themselves, albeit without guaranteeing the success of this undertaking.

-Wato Tsereteli, 2015, p.66.

I watched time drag away for weeks. I spent time laying, just bearing through it, like an illness. A song that someone had recently played on the jukebox at a bar where I was later kicked out from stayed with me: This is not what you wanted. Oh. Not what you had in mind (Brozner, 2013.) I had then tried talking to a stranger.

– Hi!

–It’s not necessary… someone else replied.

–I know it’s not necessary; may still I say hello?

–Now you understand?! I was then pushed by their friend in front of everyone. The bar door had a small sign next to it which proclaimed ‘WE DO NOT TOLERATE HATE IN THIS PLACE,’ meanwhile bouncers proceeded to pat my whole body looking for drugs on me and demanded that I faced one of many cameras before pulling me from my shirt and out the dancefloor.

‘All these racers deliberately making me restless’ echoed in my brain while I sat on the balcony revising the decisions that had got me there. One day G texted as he came down to the city from the mountains, where we had gathered some days earlier during the ritual. I met him and his villager friend S down at the parking lot and together walked somewhere for a Sunday afternoon breakfast. We found a nice restaurant under the playful shadows of yellow leaves rustling and blowing on the trees across the park. Then I felt the first sting of a distant and familiar feeling piercing through the numbness of my ongoing refuge. At night they visited, helped preparing Greek salad for dinner, and asked to join them for a ride on their rental. I offered a bottle of K’s Kisi, played Joropo del Llano, and went out confronting the noise that had had my mind circling, and my body stagnant. Suddenly I’m riding shotgun on a fast, thundering car, my companions blasting a Georgian song (Gogitidze, 2020):

A cool breeze blew in and out the windows of the car and my withered self felt stretching out, collecting itself, catching up with my exhausted mind. Their company was so contagious even the police seemed hooked on to the vibe as we all rooted together for G blowing on the roadside breath test until getting us a successful negative probe –‘More!’, ‘More!’, ‘More!’, ‘More!’, ‘More!’

Detail of Handshake, 2024. Oil on canvas (112 x 92 cm.)

Detail of Handshake, 2024. Oil on canvas (112 x 92 cm.)

Detail of Handshake, 2024. Oil on canvas (112 x 92 cm.)

Detail of Handshake, 2024. Oil on canvas (112 x 92 cm.)

We arrived at Turtle Lake and hiked in the dark up the hill on the dried mud path. At the top, S gathered wild berries from a tree which resembled another familiar figure that I had recently recalled while tracing my shadows’ outlines as they were projected onto the canvas by the studio lights behind me. We ate the fruit and watched the city glowing bright out from the bottom of the dark valley. Writing this I’ve just realized how the colors on the Handshake might echo on the glare in this moment.

S and G gathering and sharing wild berries on the hill top, Tbilisi (personal archive.)

S and G gathering and sharing wild berries on the hill top, Tbilisi (personal archive.)

Image with a series of my head’s outlines traced onto linen canvas at the studio, Tbilisi.

Image with a series of my head’s outlines traced onto linen canvas at the studio, Tbilisi.

Saludo (Handshake), 2024. Oil on linen (112 x 92 cm.)

Saludo (Handshake), 2024. Oil on linen (112 x 92 cm.)

On our way back, while crossing the river towards the studio, G mentioned the lions standing on each of the four (4) the plinths on the corners of the bridge. I had first crossed it on a hot day when M welcomed me with a tour of Tbilisi upon my arrival. The photo I took of one of them, following G‘s comment while in the car, would link my first and last paintings unknowingly.

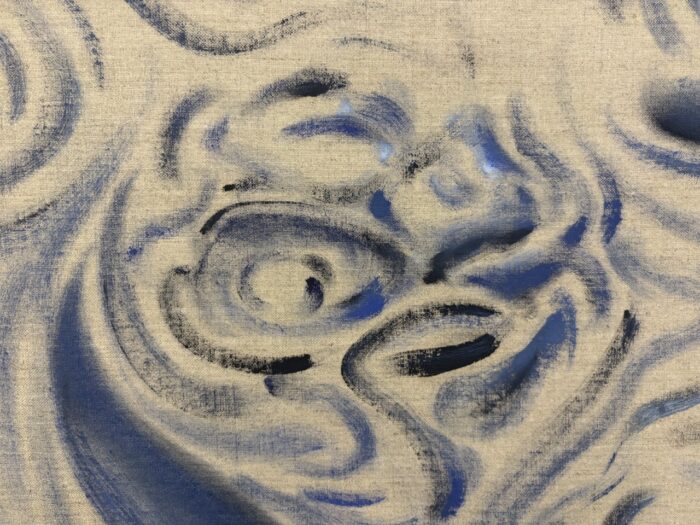

The first painting I made in the studio started out with the simple intention of remembering a cloud I’d seen one morning in the mountains. I felt it resembled the number two ‘2’. Almost immediately after making the first, dry and quick blue marks on the PVA primed linen, I saw an eyebrow appearing. I continued tracing the features around it. Before realizing it, I had outlined the portrait of a bearded man in torment resembling Laocoon’s expression of despair, as well as his Greek features.

Stamina, 2024. Oil on linen (88x 92 cm.)

Stamina, 2024. Oil on linen (88x 92 cm.)

When I sent my mother a photo of it, she said she saw a lion. One day before the show was due, I quickly outlined one of G‘s bridge lions into one of M‘s black canvases thinking about Tbilisi’s identity and history with animals. While considering how to paint the features of the sculpture in so little time, I noticed I had already done so on my first, blue painting. I have the feeling that something very personal, as well as ancient Greece’s cultural interaction with Georgia (Medea was a Georgian princess) made its way through this exercises.

Lion standing on plinth at Kura river, Tbilisi.

Lion standing on plinth at Kura river, Tbilisi.

Dark Night, 2024. Oil on canvas (34 x 40 cm.)

Dark Night, 2024. Oil on canvas (34 x 40 cm.)

Following Huxley’s method while reflecting back on his experiment (Huxley, 1954, p. 36), I opened Michael Taussig’s book on Shamanism, Colonialism, A Study in Terror and Healing and The Wild Man at random and arrived at a quote by Walter Benjamin:

Thinking involves not only the flow of thoughts but their arrest as well. Where thinking suddenly stops in a configuration pregnant with tensions, it gives that configuration a shock, by which it crystallizes into a monad. […] In this structure he [the ‘historic materialist,’ or critic] recognizes the sign of a messianic cessation of happening, or, put differently, a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past.

– Michael Taussig (1986) p. 200.

Relating to Benjamin’s matured view on the role of the critic when engaging with the ‘dialectical image’, Taussig mentions the intrinsic value that fluid, popular images–such as Our Lady Remedies, in Santiago de Cali (Colombia)–, take on the daily, as well as the mystical social life. The coined monad, often discussed in philosophy and theology, seems like a formless unit which somehow shapes the course of our reality. Gathering how the visual artwork holds the ambiguous experience between myself and others as a fluid anchor of the many participants helping build meaning through it, I wonder if painting isn’t the material expression of such a remarkably complex event.

Installation view of Stamina (left) and Handshake (right) exhibited in Dark Night at project space in Fabrika, Tbilisi.

Installation view of Stamina (left) and Handshake (right) exhibited in Dark Night at project space in Fabrika, Tbilisi.

References

Ajerman, M. Broomsticks and Bedknobs, A Talk on Paula Rego. In: Painters’ Forum, Meeting with Geraint Evans. 15.11.2024. MA Talk. Recording on Microsoft Teams. Camberwell College of Art: London.

Bronzer, G. (2013) Bad Kingdom. Moderat. Monkeytown Records.

Gogitidze, M. (2020). Vici Daggale (Single) Lyrics Translate. (29.03.2024) Translation by Sumonishvili, S. Available at: https://lyricstranslate.com/en/vitsi-dagghale-i-know-i-have-tired-you-out.html#songtranslation. (Accessed on 13.11.2024.)

Helguera, P. (2011) Education for Socially Engaged Art; A Materials and Techniques Handbook. New York: Jorge Pinto Books.

Huxley, A. (1954) The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. London; Vintage.

Merleau—Ponty, M. (1948) The World of Perception. London: Routledge Classics, 2008.

Paula Rego: Letting Loose. [Exhibition]. London: Victoria Miro Gallery. 22 September 2023 – 11 November, 2023.

Philip Guston. [Exhibition]. London: Tate Modern. 05 October 2023 – 24 February, 2024.

Rancière, J. (2009). The Emancipated Spectator. London; Verso.

Taussig, M. T. (1986) Shamanism, Colonialism, A Study in Terror and Healing and The Wild Man. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Thompson, M. (1989) On Art and Therapy; An Exploration. London: Virago Press.

Tsereteli, W. (2015) “Argonauts. Topographic Transcendence; Becoming Universal Without Ceasing Being Particular”. In: Neuburg, K. (ed), Pranz, S. (ed), Soselia, A. (ed), Tsereteli, W. (ed), Vogler, J. (ed), and Weiss, F (ed). Tbilisi; Archive of Transition. Tbilisi: Niggli, (p. 63-78).

Watts, M. A. (1980) Chance: A Perspective on Dada. University of Iowa: UMI Research Press. University Studies in Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 9.