MA CAMBERWELL UNIT 2

(Click on images to view them in full on your screen)

On reliance

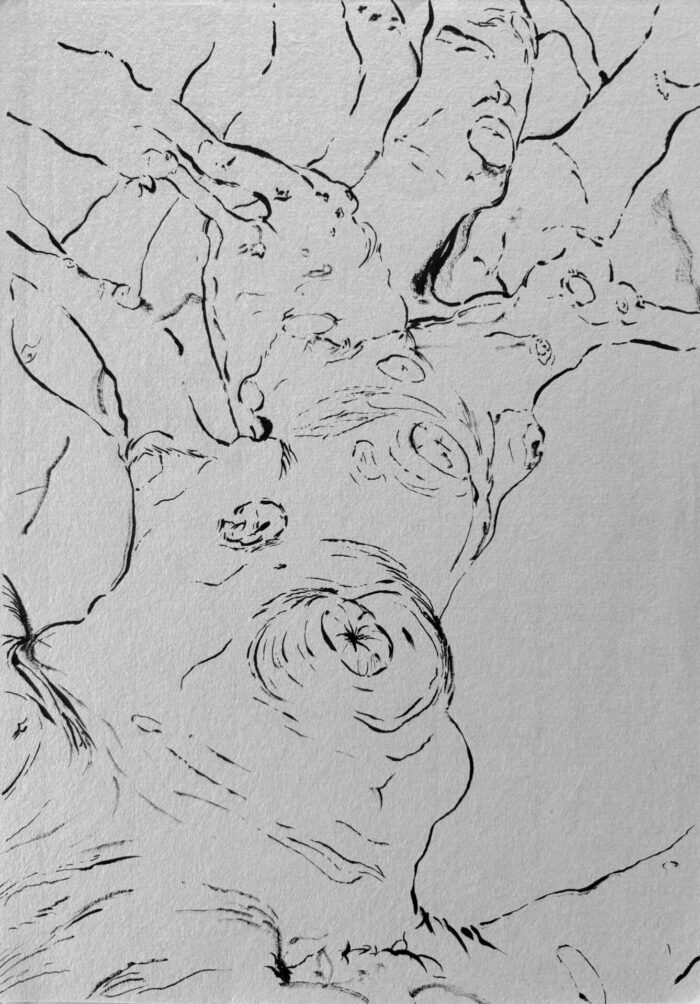

Staring Contest # 2. Copper Beech Tree, Lucas Gardens (Peckham, 2024)

Black Indian Ink on Japanese paper

‘Would you be able,’ my wife asked, ‘to fix your attention on what The Tibetan Book of the Dead calls the Clear Light?

I was doubtful.

‘Would it keep the evil away, if you could hold it? Or would you not be able to hold it?’

I considered the question for some time.

‘Perhaps,’ I answered at last, ‘perhaps I could – but only if there were somebody there to tell me about the Clear Light. One couldn’t do it by oneself. That’s the point, I suppose, of the Tibetian ritual – someone sitting there all the time and telling you what’s what.’

After listening to the record of this part of the experiment, I took down my copy of Evans-Wentz’s edition of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, and opened at random. ‘O nobly born, let not thy mind be distracted.’ That was the problem – to remain undistracted. Undistracted by the memory of past sins, by imagined pleasure, by the bitter aftertaste of old wrongs and humiliations, by all the fears and hates and cravings that ordinarily eclipse the Light. What those Buddhist monks did for the dying and the dead, might not the modern psychiatrist do for the insane? Let there be a voice to assure them, by day and even while they are asleep, that in spite of all the terror, all the bewilderment and confusion, the ultimate Reality remains unshakably itself and is of the same substance as the inner light of even the most cruelly tormented mind. By means of such devices as recorders, clock-controlled switches, public address systems and pillow speakers it should be very easy to keep the inmates of even an understaffed institution constantly reminded of this primordial fact. Perhaps a few of the lost souls might in this way be helped to win some measure of control over the universe – at once beautiful and appalling, but always other than human, always totally incomprehensible – in which they find themselves condemned to live. (Huxley, 36-37)

: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :

—I’ve had trouble coming to the present moment for some time. In various situations, I easily drift towards hypothetical alternatives, into my mind, withdrawing from what’s actually around me. In a film about Syd Barrett, who was former painting student at Camberwell, a previous flat mate of his, Duggie Fields, says in an interview that after some time together, it was all too obvious what Syd was always doing opposite the wall that used to separate their bedrooms. “I was never aware of Sydd as being a prolific worker, should we say, while he was here. I mean, it would be spasmodically. (…) I knew that he was lying in bed, sort of thinking… My interpretation is that, while he lay there, he had the possibility of doing anything in the world that he chose. But the minute he made a choice, he was limiting his possibilities. So he lay there for as long as he could. So he had this unlimited future. But, of course, that is a very limited present.” I used to take part in a similar ‘identity’, and I would cherish it as my own special virtue. It still gathers a learned tendency and has played a role while settling in an overwhelming city as a student, once more. But I don’t see the point in identifying with spending my time, like a good friend of mine once said, away. I really don’t have to define myself in any way. On the contrary, I wonder how many others must share it as a coping mechanism in these times of accelerated media consumerism, where we’re daily told to consider an unlimited variety of alternatives waiting for us, like Martin Heidegger would say, ready at our hand. And I wonder, how can I train myself to remember the value of perceiving and making sense of the world around me. In doing so, my first lesson has been realizing how different my thoughts are from what I thought they were when expressing them.

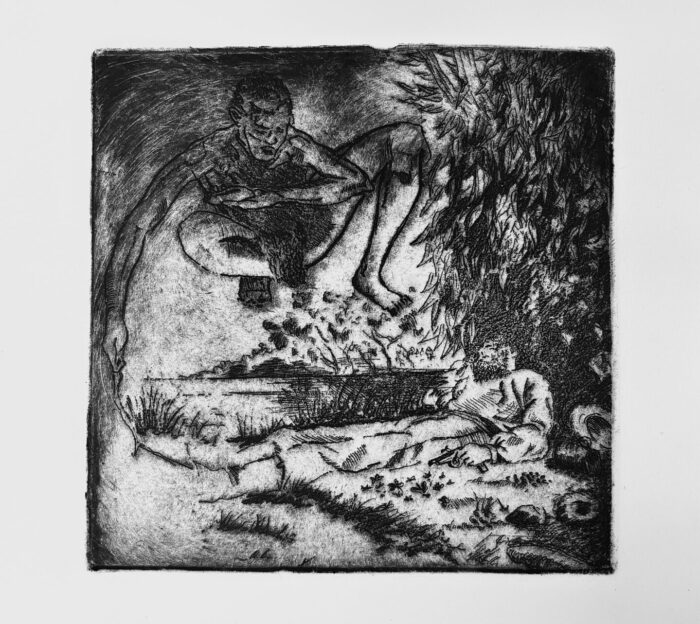

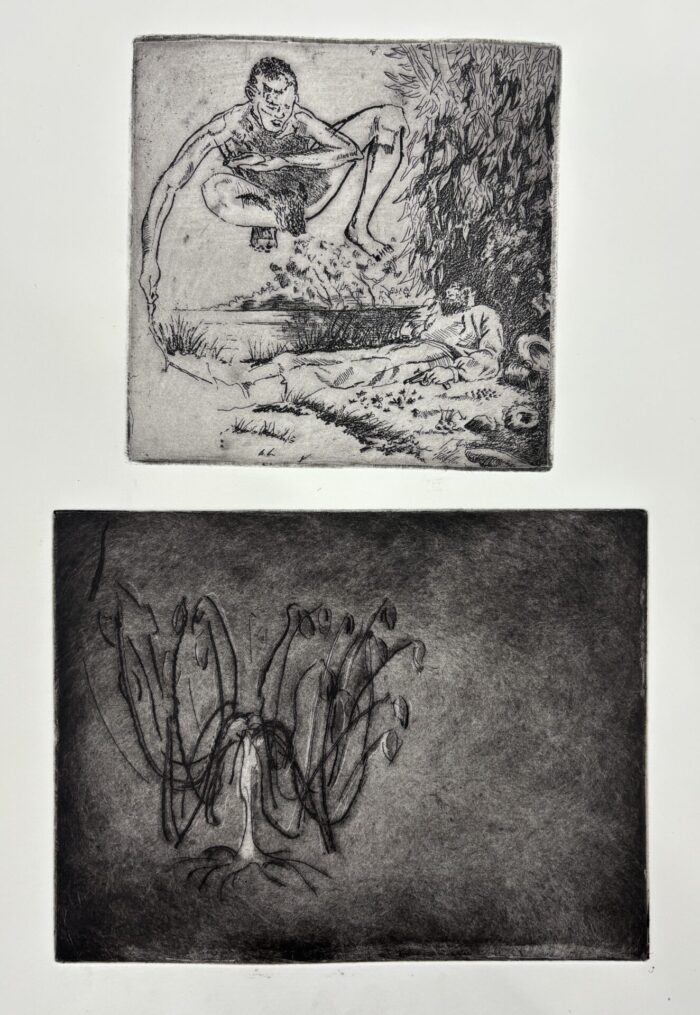

Riverbank (Etched in 2010 / Printed in 2024)

Hard ground etching on cotton paper

(40 x 32 cm)

Context 1: Falling: Group Reading with Leora Brook

—While reassessing the freefall and the sublime in present-day developments on perspective and warfare in Hito Steyerl’s In Freefall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective, each one was asked to briefly describe their own practice in relation to her text. I presented the active role of ‘chance’ as a precept in my studio work and, in response, Leora quoted Hito on the considerations of engaging on landscape without a horizon, or reference point of departure: “Falling means ruin and demise as well as love and abandon, passion and surrender, decline and catastrophe.” (Steyerl, 28). Before writing this, Hito proclaims: “A fall toward objects without reservation, embracing a world of forces and matter, which lacks any original stability and sparks the sudden shock of the open: a freedom that is terrifying, utterly deterritorializing, and always already unknown.” (Steyerl, 28).

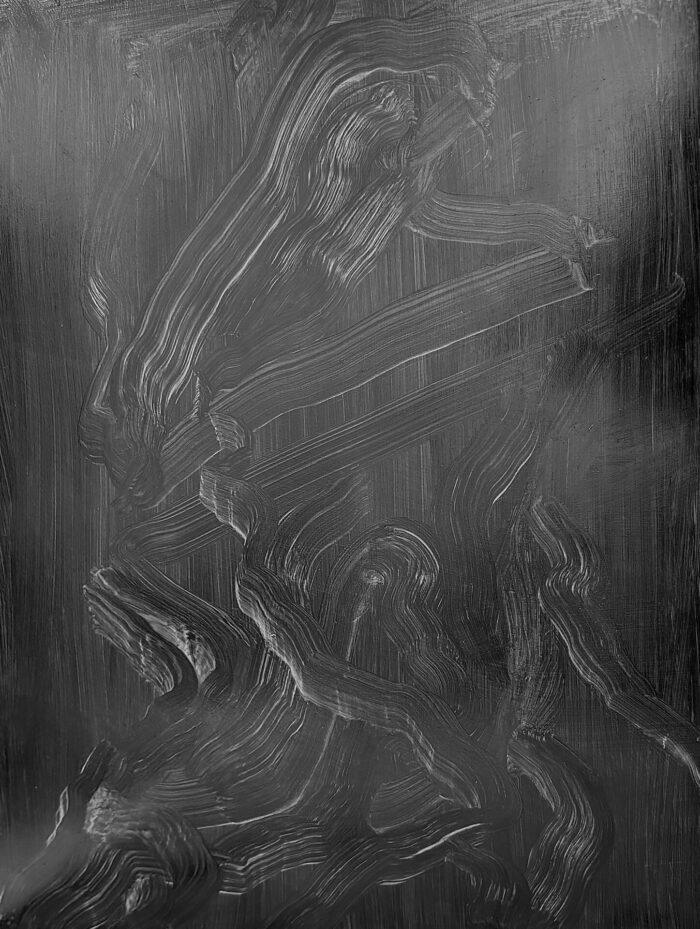

Painting in process; before what Manuela Ammers refers to ” the Affective Gesture” emerges

Oil on Board (39.5 x 35 cm)

—The perpendicular margins on the corners of the e-journal pages locked the text on my computer screen like the outlines on a flying F-16’s ‘heads-up display’ employing guns at a radar-locked target. Discarded paintings locked on my screen, and then I thought about stepping away from the familiar ledge, thinking about how relying on chance has proven an unsustainable methodology for me. I’ve become used to waiting before jumping for too long, looking down, replaying infinite falls into an abyss while hurting my hand from holding tight on to the metal handrail but not feeling it.

Discarded work, oil on Board

—Hito continued: “Falling is corruption as well as liberation, a condition that turns people into things and vice versa. It takes place in an opening we could endure or enjoy, embrace or suffer, or simply accept as reality.” (Steyerl, 28). If we equated falling with the act of chance, which is what randomness requires when, for example, ‘rolling’ the dice, we could say it has been explicitly put into practice of pictorial and material associations by the Surrealists over a century ago. For those who Marie Anne Watts refers to as the ‘mystically inclined’ (Arp, Ball, Richter, Ernst), chance selection allowed them to surrender to and access greater natural laws of “unknown, universal correspondences, to an order beyond any construct posited by Western casual and logical thought” (Watts, 4). Pushed by a challenging and intellectually stimulating environment, I have come to believe that, however randomness plays a definite part in our reality, it isn’t enough to observe the conditions of a fall a priori, without there being an actual subject of interest falling. Whether it be an object, a theme, a rolling of dice, “one couldn’t do it by oneself, there must be “someone sitting there and telling you what’s what” (Huxley, 36). As in a game, like Anna Bunting-Branch suggests, the parameters must be identified, there must be some kind of guide—some body, some other, some person, plant, entity, experience, book, teacher, community, or friend— in becoming present, remaining undistracted, reminding oneself on what to look after, on how to fall.

Discarded layer, oil on board

—The ‘guides’ that we encounter while falling appear during sudden turbulence, an unexpected drop in pressure, a warm current or an unexpected breeze. When identifying them, they all require that we become present in how they make us feel. Some guides have led me to the next, many giving out the same advice in different forms, signs, words, and languages. It’s hard to sometimes distinguish between the nature, or the laws that act upon falling and the subject of interest, or the falling body. As an exercise to help identify the latter, what follows (and precedes), projects a stream of consciousness guided through a counseling session with a few of references in the search for boundaries that relate to painting as a language based simultaneously on perception and interpretation: : : :

Context 2: Kelleys’s ‘Working tropes’

—I’ve heard people mention the ‘instinct’ when referring to a ‘gut feeling’ as an alternative ‘inner’ guide from which to operate against the usual rational mind when deciding under specific circumstances. These comments came about at a time when wondering about ‘intuition’, and so I would ask what makes them different between each other as mediated by the body and opposite to what Maurice Merleau-Ponty called the ‘ambiguous, rational mind’.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “Rather, as in the perception of things themselves, it is a matter of contemplating, of perceiving the painting by way of the silent signals which come at me from its every part, which emanate from the traces of paint set down on the canvass, until such time as all, in the absence of reason and discourse, come to form a tightly structured arrangement in which one has the distinct feeling that nothing is arbitrary, even if one is unable to give a rational explanation of this. (Merleau—Ponty, M. 72).

—In Sink And Swim and Fight and Flight, Dominique Carpentier (MA, Digital Arts, Camberwell, 06’) presents “Two films exploring the psychology of aggression and containment”. In her first video, a swimming figure appears to struggle to reach the surface as it alternates between locomotive and static motion underwater. In her second short, she alternates a selection of quotes with separate takes of a naked male figure engaging in a Fighting stance in slow motion. Her performance work delivers very simple narratives through audio-visual media to convey a feeling through both metaphor (e.g drowning) and form (e.g slow motion perception of time) experienced during the “Fight, flight or freeze” modes activated by the Sympathetic Nervous System at threat (Chong, 120).

Maurice: We shall see that, like all works of art, such a film would also be something that one would perceive. Beauty, when it manifests itself in cinematography, lies not in the story itself, which could quite easily be recounted in prose (…) Taken together, all these factors contribute to form a particular overall cinematographical rhythm. (…) Then, as now, this viewer will be left not with a store of recipes but a radiant image, a particular rhythm. Then and now, the way we experience works of cinema will be through perception.” (Merleau-Ponty, 98-99).

May 8

—Yesternight, I witnessed a stabbing in the front door of my council building unit in central Peckham; the Primrose House. Mid May, around seven PM, I was then cooking dinner. To my left, the kitchen window overlooked the heavy blue-steel entrance on the ground floor and was open in full like letting the spring evening sunset sink in and out the smell of boiling basmati rice and ripe tomatoes. Standing there, like waiting, I heard a sudden, violent howl. I couldn’t describe the sound except compare it to what I thought was happening in the first instance. It sounded like a dog fight, and I didn’t realize it wasn’t until a long silence creeped back in right after. I stood in shock, and if anything felt deliberate, it was not to look out; I stood watching the remaining bubbles burst through oily, basmati rice. “You’re bleeding!” echoed a woman’s voice in distress. I looked out and, in the distance, two figures wearing black hoodies and bumper jackets ran past the curb and disappeared around the corner. “You’re bleeding!”, said the woman once more. She was wearing a brown turban, a floral dress and was holding a brown leather handbag and a large, pink iPhone against her ear while facing the blue gate. A young man with braids was leaning against it; his face was covered with a blood-stained covid mask. He tried was reaching for something on the door and struggled to stand. I watched, my thoughts clouded, and I stood still with a sharp sting up my spine and the thought of danger. My flat bell rang repeatedly and my body began to turn erratically from the window and towards the stoves until I stood back, again pretending to cook the burning rice and the spluttering tomatoes like I was too busy to buzz anyone in. I didn’t even notice the police’s sirens as they pulled in.

Canvass where I’ve placed the surplus oil paint left in my palette when painting my other paintings (2024)

Oil on canvass (60 x 45 cm)

Mike Kelley: The parts you can’t remember are called ‘Missing time’; the part of trauma you don’t remember, you gotta recover it. Sense always comes after the fact. Categories start to slip and that produces what I think is a sublime effect, or produces humor. Both things interest me. And I guess I am interested in sublime play and sublime humor. Dark humor. Sense always comes after the fact in my work, and so I try to make it at first glance acceptable.

Peg Rawes: For Henri Bergson, intuition relates to the “simple act which has set analysis in motion and which hides behind analysis”, as a reverse procedure which reverses the process of analytic reasoning and “emanates” from another faculty that is not reducible to analytic methods, and therefore, violently introduces an alternative procedure which enables the generation of fluid concepts capable of following reality in all its windings and of. Adopting the very moment of the inner life of things.” (Rawes, 145)

—None of it felt intentional, though. I just watched my guilt as dozens of first responders arrived; officers cut off the victim’s clothes with scissors, stabilized the bleeding before putting him on a stretcher, into the ambulance, and away.

Dominique Carpentier: “I Shall be a castaway. The beast in me, is caged by frail and fragile bars. Restless by day, and by night, rants and rages at the stars. God help the beast in me” —Nick Lowe

—“But what could have you done?” Asked the policeman who instructed me across the blood-stained corridor out the building on my way to the Peckham Pulse Leisure Center after deciding on making it to an unsuccessful medium-lane swim. On my way, I shook the hand of a man who asked me questions about what had happened and which I had no clear answer to. “What could have you done?” asked my compassionate course mates after I unexpectedly growled an awkward noice instead of asking a question during a creative talk on sound and podcasting as alternative means of critical reflection by Roshni Bhagotra. During her talk, she had discussed the ‘politics of listening’ while playing Mango frequencies for us and inviting to ‘speak without objectifying’, to ‘confront our own projections’, to ‘promote conversation’, and to ‘break down barriers’.

Manuela Ammer: “Examine the two statements, ‘Help!’ and ‘I need help’. The fist language is a cry; the second, a description. Only the cry, art, rather than the description or criticism, is primary. The cry is stupid; it has no mirror; it communicates. / I want to cry / Why should anyone listen? / —Kathy Acker (“Models of Our Present”. Artforum 1984).

—I’m thankful to everyone who responded to my cry out of context. Some catharsis took place with my reaction. And I wonder how everyone else in my building has dealt with this episode since, because I feel there was just something left to tend to: The building does not look the same to me now. Only it wasn’t just me witnessing it; there’s trauma left to process within the community where I’m living in. But it has been left broken, fragmented, unattended, resulting in each one carrying within their own shard of it when venturing outside the door. Mine has left my body making noises of distress, one of my body’s coping mechanisms, screaming inwardly and outwardly for some of the reassurance we were all left to look for in other people. Perhaps my body reacted for me during this confusing ‘missing time’.

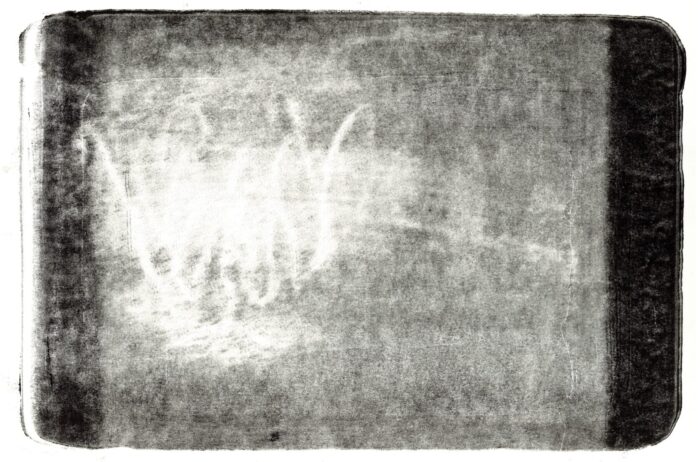

Black and white image of “Moving Forward” in process: outline of a figue or “cliché” emerging while painting.

Oil on board

(47.5 x 37.5 cm)

Manuela: Gene Swenson who, during the exhibition “The Other Tradition” at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, 1966, made an “attempt to find a niche for a more inclusive conception of the body within an increasingly narrow and constricting modernist paradigm. Like [Lucy] Lippard, Swenson considered the psychological interpretation to which modernist painting, in particular, had been subjected problematic; his answer, however, was not to negate the existence of emotions or to seek the erotic in the abstract. Rather, he turned emphatically to our visual ‘common property’—to the collective feeling that, having been refined as an object or image, has become cliché. He saw the potential of the artistic works he championed not in their formal innovativeness but in their functionality; they defined a new relationship between art and viewer that had implications both and social: ‘The paintings of the other tradition. . . might be said to objectify experience, to turn feelings into things so that we can deal with them.” According to Swenson, the images and technologies that mass culture provides are not threats but tools. The new subject will not retreat into the why but will engage with the how; it will use those images and technologies to learn about both its individual workings and the workings of society in general. The question of how instills agency.” (Ammer, 90)

View of Window at Collioure (left) and Interior with Goldfish (right)

Henri Matisse

1914 (116,5 x 89 x cm) and 1914 and (147 x 97 x cm)

Centre Pompidou, París (Visited 2024)

Mike: When I was working with stuffed animals I wanted to work about the dialogue going on in the 80s with ‘commodity culture’. But, when looking at all these stuffed animals, everyone thought it had to do with my abuse. And I thought it was very interesting. Then I decided: I have to make all my work about my abuse. Not only that, about everyone’s abuse. This is our shared culture.

(Right) Copy of Matisse’s Interior with Goldfish (2014)

(147 x 107 cm)

Bogotá

Maurice: We do not start out in life immersed in our own consciousness, but rather from the experience of other people. I never become aware of my own existence until I come into contact with others (…) The adult himself will discover in his own life what his culture, tradition, education, and books have taught him to find there. The contact I make with myself is always mediated by a particular culture, or at least by a language that we have received from without and which guides us in our own self language. (Merleau-Ponty, 66)

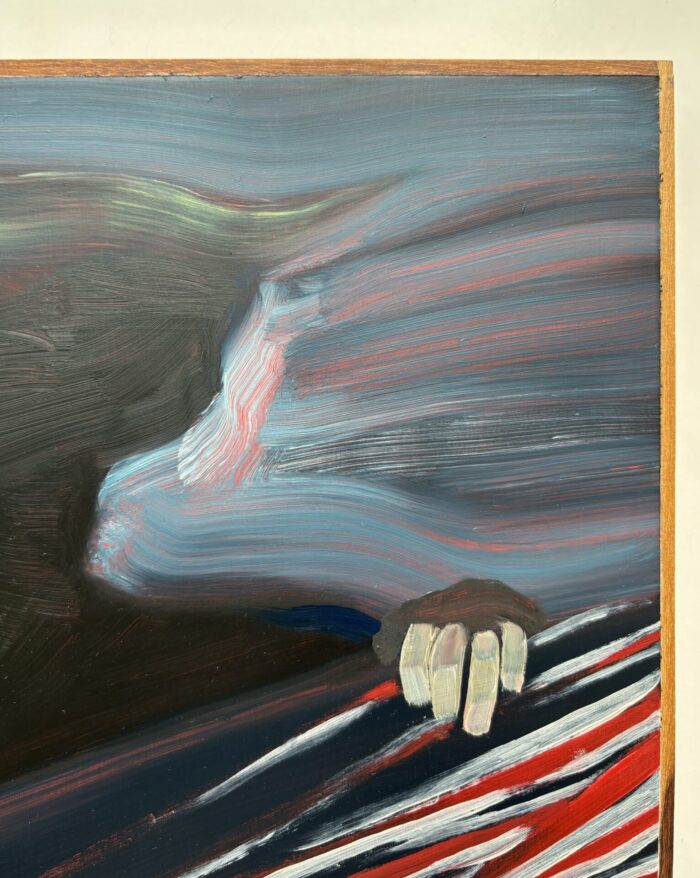

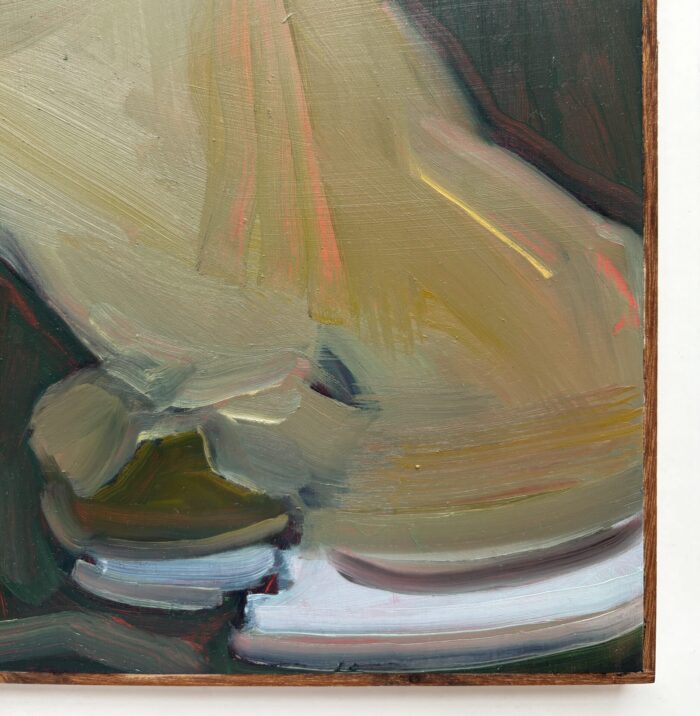

Moving Forward

Detail (Lower left corner 2024)

Oil on board (47.5 x 37.5 cm)

—It appears to me that, If one can be attentive to the process of indiscriminate mark-making on a surface, through it, unexpected content, or unexpected clichés emerges. Form and color start looking like something else, although it might be nothing other than these two essential properties laid on a surface on a fluid medium. At these times I wonder, should I follow suggesting these clichés to the point of illustration? Do I leave them open? Or, do I go the other way, avoiding whatever it is that appears in my head as a reconfiguration of the abstract marks in front of me?

Mike: I see all art as being a kind of materialist ritual.” (…) “All motivation is based on some sort of repressed trauma. I make something… my work is very reactive: I get a response that I had no idea that I was going to get. I don’t reject it, I embrace it, I run with it, you know? That tells me what to do.

Moving Forward

Detail (Upper right corner 2024)

Oil on board (47.5 x 37.5 cm)

Manuela: While [María] Lassnig sought to generalize individual bodily sensations in pictures, [Lee] Morton turned commonplace images into images that resonate with affect. The feminism of the 1970s thus made the question of the body in/of painting an explicitly affective affair, a matter of emotional investment that is clearly recognizable as such at the level of representation itself. (Ammer, 93)

—And what do you mean by affect according to the modernism that operated almost exclusively on ‘optical experience’?

Manuela: Opposite to images but rather “sensuous facts”, which today is called affect (the presence beneath representation, beyond reprersentation). (…) Deleuze diagnoses one of the problems peculiar to contemporary painting as the multiplication of images of all kinds both around us and in our heads: We are besieged by photographs that are illustrations, by newspapers that are narrations, by cinema images, by television images. There are psychic clichés just as there are physical clichés—readymade perceptions, memories, phantasms. There is a very important experience here for the painter: a whole category of things that could be termed ‘clichés’ already fills the canvas before the beginning. It is dramatic.” Because the canvas is occupied even before the painter has applied so much as a single brushstroke, any belief in the figurative, in working with the cliché, is doomed to failure. The cliché can be fought only ‘with much guile, perseverance, and prudence. (Ammer, 86)

Moving Forward

Detail (lower right corner 2024)

Oil on board (47.5 x 37.5 cm)

Mark: All writing is associative and comes from my own experience, but it’s very hard say to disentangle memories or films or books or cartoons or plays. . .um: “real experience”. It all gets mixed up! So, in a way, I don’t make such distinctions. I see it all as a kind of fiction.

“Slow Burn” in process. Appearance of “affective gesture” before image is configured. Oil on board

Manuela: [Francis] Bacon’s Path,” as Deleuze calls one chapter of his book [The Logic of Sensation (1981)], is neither optical like abstract painting, nor manual like action painting.” His guile lies in the way he fights through all the clichés of the figurative in order to find a true, immediate and improbable ‘second figuration’ obtained as an ‘effect of the pictorial act’.” “Deleuze describes the pictorial act as the intrusion of the world (random manual mark making) into another clichéd figuration, visual or actual); the former confuses the latter, purges it of the narrative and visual mud and establishes a new order of clear sensation.” (…) Deleuze sought to defend the truth of painting on the grounds of its immediate, and hence unmanipulable, corporeality.” (Ammer, 88)

Controlled Burn (Stills of video Installation, 2022)

Julian Charrière

Seen at Our Ecology, Towards Planetary Living.

Mori Museum, Tokyo 2023-24 (visited in 2024)

Context 3: Cutting through the diplomatic spectacle

May 17

Sometime ago I remember someone telling me about some documentary. I think it might have been a Werner Herzog documentary. I gather it was about a community of misfits where its members shared a rare neural condition—perhaps generally considered a disability—by which, if I’m not mistaken, one can either be partially or fully incapable of relating words and sentences with their corresponding categories and meaning; it related to a certain inability to interpret verbal language. During a certain scene, the whole group sits to watch a standard, stern statement given to the public by some politician, possibly Ronald Raegan, on TV. All along, the crowd turns laughing in crescendo, making it clear and clearer that they’re actually getting a lot from the speaker’s delivery, just not much from the message that they’re trying to convey onscreen through words. Oblivious to the scripted speech, the members of this community allegedly react directly to all the non-verbal language (microexpressions, tone of voice, body language, etc.) which, I would believe according to Herzog, is directly indicative of the TV speaker’s hesitancy to transmit an unsettled message; indicative of the farce being said and a caricature of the Politician. It’s like the subject of interest, the misfits, have been left to rely socially on their haptic (sensory) capacities to receive communication, therefore learning to call the bluff of diplomacy seeing right through the trenches of rhetoric.

Moving Forward (2024)

Oil on board

(47.5 x 37.5 cm)

—What is verbal communication doing apart from what we are actually saying? I guess there are layers of meaning in our rhetoric and there are very direct, like affect is direct, body gestures that cut through performativity.

Owen Herbert: If there is one British thing, it’s we never say what we mean in ages. Instead of asking how you’re doing, we ask about the weather. And that way we both know if we’re engaging with someone sane and then have a conversation.

—Where is my body in relation to the work? Maybe I want to say the body has its own language, and speaks for us when we cannot speak for ourselves. Ultimately, in the process of arriving at my surroundings, the creative act proves that our most heavily regarded guide with which to encounter the falling object must be to inhabit vehicle with which we fall, that is our own perceiving body.

Slow Burn (2024)

Oil on board (Installed at Copeland Gallery)

(38.5 x 27.5 cm)

Woks by Yuanwei Huang (Here, Together), Xuan Hew (The Alps – Les Grandes Platieres), Owen Helbert (There’s a Reward for Getting Underneath), Ernesto Soto Madriñán (Slow Burn), Xuan Guan (Don’t Know How to Lie), Matt Reed (Views I), Tianqui Gong (At Night, a Window to Memories), Chuhamo Jike (Echoes), Quianhe Dai (Frame)

Installation view: Where We’re Coming From, Copeland Gallery, Peckham, May 2024.

Contributors (bibliography):

Manuela: Ammer, M. “How’s My Painting?” (Judge, Please, Don’t Judge Me)”. in Painting 2.0 Expression in the information Age Gesture and Spectacle, Eccentric Figuration, Social Networks. Ammer, M. Hochdorfer, A, and Joselit, D. Museum Brandhorst, Bayerische Staatsgemaldesammlugen. London; DelMonico Books, 2016 (88-102).

Dominique: Carpentier, D. Sink And Swim and Fight and Flight, Dominique Carpentier. MA, Digital Arts, Camberwell. London: Library resource, 2006.

Chui Yee Joy Chong: Chong. C . “Why art psychotherapy? Through the lens of interpersonal neurobiology: The distinctive role of art psychotherapy intervention for clients with early relational trauma”. United Kingdom: International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape, 2015. Vol. 21.

Owen Herbert: Herbert, O. Semillero: Critical Reflection Salon, second meeting. London, Camberwell College, 2024

Shabaka: Hutchkins, S. “Managing My Breath , What Fear Become”. Featuring Saul Williams. Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace. London: Impulse! Records, 2024.

Aldous Huxley: Huxley, A. The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell (1954). London; Vintage 2004.

Mike: Kelley, M. “Memory: Mike Kelley, Susan Rothenberg, Josiah Mcelheny, Hiroshi Sugimoto”, Art 21 [DVD]. New York: PBS, 2005.

Maurice: Merleau—Ponty, M. “Art and The World of Perception”. The World of perception (1948). London: Routledge Classics, 2008.

Peg Rawes: Rawes, P. Space, Geometry, and Aesthetics; Through Kant and Towards Deleuze. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Hito Steyerl: Steyerl, H. “In Freefall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective”. The Wretched Screen (undated). Sternberg Press, e-flux journal.

Marie Anne Watts: Watts, M. “Introduction: Chance and Dada”. Chance: A Perspective on Dada. University Studies in Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 9. University of Iowa, 1964.

Learning from the other: Helen Knowles

Testing beyond the studio practice

In February 2024, artist, curator, and PhD candidate Helen Knowles agreed to meet for tea after delivering her cross pathway talk mediated by Computational Arts pathway leader Max Dovey. In general terms, her work “relates to the way the immaterial meets forms of life, particularly in the social realm, teasing out questions of responsibility, autonomy and ethics in relation to technology, artificial intelligence, and the non-human”. Days before her talk, I reached out to her via email asking for advice on how to work with and write about certain subjects that “I have been regarding very closely in my recent life”, and added that I had resonated with her titles and images. I added that her confidence on working with such themes and communities had struck me: “it can be difficult [for me] to distinguish what relates to my personal experience, and what belongs elsewhere; especially when trying to be very mindful of the ethics regarding working with Indigenous cultures and (their) knowledge. She replied: “I guess after a long and round about journey (still ongoing) there will be bumps and bruises but staying respectful and aware, transparent and open to change, discussion and challenge, is important.”

After her talk, we discussed briefly her latest work “Trust the Medicine”, and each of our shared experiences with members of the Cofán community in Putumayo, Colombia. Our meeting led towards collaborating her ongoing project Indexed Beings. I agreed and met with for it. The video edit shows a performance conversation between the Herbarium’s Director, Jorge Contreras with a member of the Colectivo Selvas Vivas, Manuel Mueses, in Puerto Guzman. In a polite encounter, the scientist, Jorge, and the indigenous gardener, Manuel, exchange opposing views on plant collection of samples for scientific knowledge and ecologic preservation.

Helen Knowles gathering Elderflower in Hampsted Heath, London

In thinking about what language, art, and cultural rituals do for a society, I have been thinking about how the exercise of translating Jorge and Manuel’s conversation has allowed me to really listen to their words beyond the unconscious judgements I believe to carry with me as a western thinker. In trying to help Helen convey indigenous thought by capturing the subtleties in a rather brief conversation about plant life and their utility, I’ve taken the opportunity to listen carefully. The more we play, and replay the video, and discuss with Helen about what is it that Manuel is trying to say, the more I can make sense out his point and though. As part of one of the many oppressed, exploited, and massacred ethnic minorities who, to this day fight to recover from the rubber trade in the past two centuries, and the abuse and stigmatization of their farming traditions (amongst being subject to many other social and political oppression), he speaks clear to his belief and understanding of plant-life in relation to human-life in clear, nuanced Spanish. He argues with clarity through all of his mannerisms, idioms, and accent about his suspicion towards the Scientist’s practice and, in the words of Knowles, the interests that it may serve.

Riverbanks and Ghost Tree

Hard ground etching on cotton paper (40 x 32 cm)

Etched in 2010-2024 / Printed in 2024

Staring Contest # 1. Copper Beech Tree . Lucas Gardens, Peckham (2024)

Black Indian Ink on sketchbook

MA Final Degree Show Proposals

With a little over 5 weeks to prepare for the MA final show, I will be working simultaneously on three projects in order to present at least one of them to the public.

- A 4.50 x 2.00 meter canvas hanging on my studio wall. I has been prepared with rabbit-skin glue, venetian red pigment and hangs from 6 eyelets dyed on the top. I’ve been considering ways of engaging with it (painting it) and how to display it.

Canvas in the studio space (Installed vertically). 250 x 200 cm. Cotton duck, eyelets.

2. Finishing painting the two remaining boards I brought with me in order to complete the series of six medium-format paintings; all different size and subject. I’d like to present them together.

Moving Forward (2024)

View at Copeland Gallery on “Where We’re Calling From”, May 2024

Oil on board (47.5 x 37.5 cm)

1 of 2 boards in process (6 boards in total) 2024. Oil on board (48 x 39.5 cm)

3. Making a digital randomly-based animation from the 51 lithographic prints of th Ghost Fig Tree.